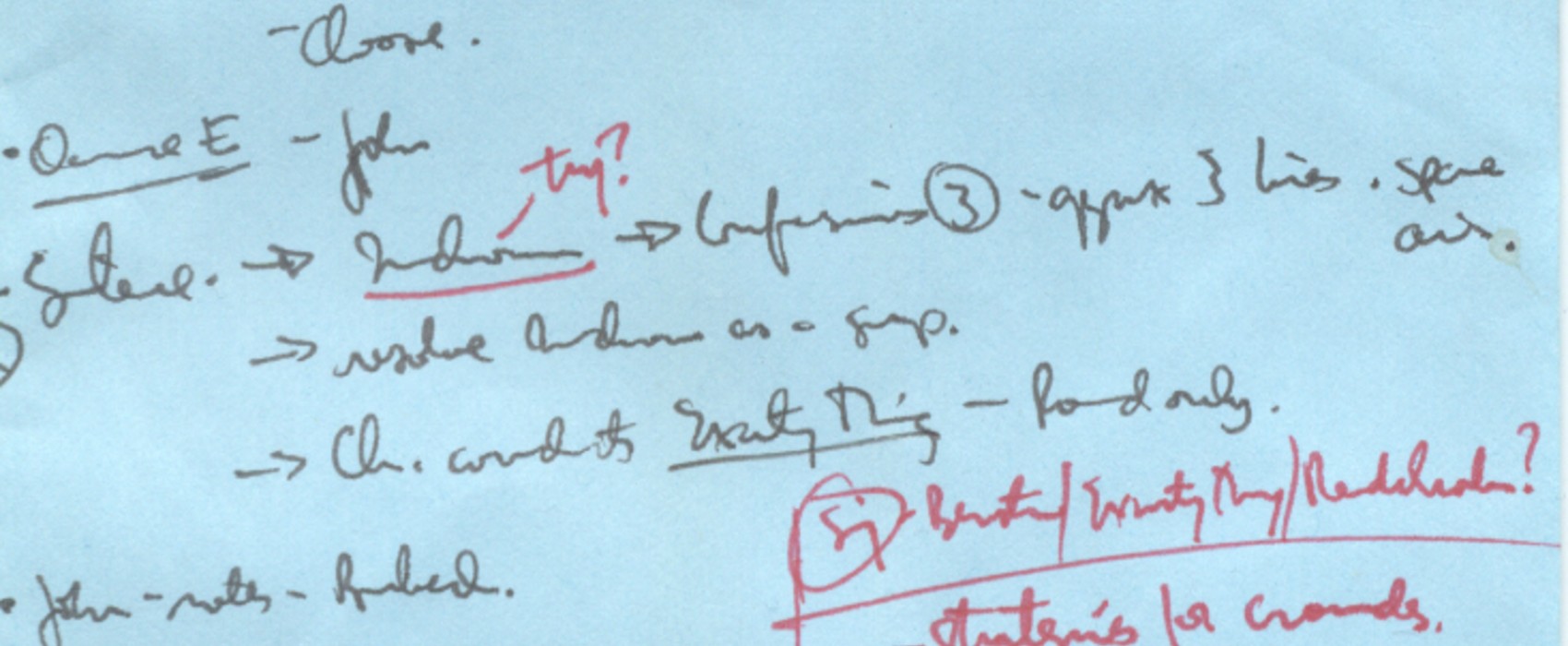

Image: Brian’s handwritten notes

The Art of Commissioning

By Brian Quirt

There are few greater pleasures than reading the first draft of a script you’ve commissioned. I had that pleasure this morning and afterward reflected on the commissioning model we’ve developed at Nightswimming. I also recalled a session on commissioning at a LMDA Conference many years ago. Morgan Jenness, a New York-based dramaturg and now agent, led the session. Her essential message about commissioning: don’t do it. I tend to agree with her.

Here’s why I agree, and here is why Nightswimming does it anyway.

A commission is too often a commercial relationship not an artistic one. But it frequently wears an artistic disguise – that’s what can lead to disappointment, misunderstanding and conflict.

It’s a commercial relationship because the context is generally about product rather than process or content. In fact, most commissioning contracts are actually about judgement: at this date in the future we (the theatre) will decide if what you (the creator) have written is worth what we invested. Is it worth the investment of still more time, energy and money?

In certain situations, that sort of contractual arrangement works just fine, particularly if the writer is confident about her work and clearly understands the gamble the commission actually represents to both parties.

In too many situations, however, the parties misinterpret the relationship. The artist believes, or is led to believe, that the theatre (through the commission) is committing to them and their script. And the theatre believes it is doing the artist a favour in offering the commission. In reality, the theatre is gambling a sum of money (a sum usually too small for the work it applies to) to have the right to produce the script if they like it.

There may be a lot of talk or even clauses in the contract about workshops, but what a commission contract really comes down to is this: 1) the playwright hopes the theatre will like the manuscript enough to proceed to the next phase of development; and 2) the theatre hopes they like it enough that they won’t have to find a diplomatic way to drop the project.

The worst case is when it becomes an adversarial relationship in which the writer struggles to find time to write and meet the deadline and the theatre tries not to nag too often. And both hope it will all work out. Sometimes, of course, it does.

Still, it’s not a very solid artistic basis for a long term working alliance.

You’d think that I would be completely against commissions. In fact, all Nightswimming projects begin with a commission. Rather than reject the idea of commissioning, we have developed a way to do it that works for us and for the artists we commission.

Why do it at all? Because, quite simply, a commission puts money where it is most needed: in the playwright’s pocket.

But rather than rely on hope, we try to build our commissions on faith. We believe that the artist will, in time, create a work with us that we can develop through to a premiere production. We commit to our commissions for the life of the project, however long that is, not just to the next option deadline. In doing so, we become advocates for the project, as eager as the commissioned writer for it to move forward and partners in all the hurdles to get it there.

Nightswimming became a commissioning company ten years ago. What I observed during my years at producing theatres was that commissions rarely work when there is no significant relationship between the theatre company (or its Artistic Director) and the commissioned artist. A commission can be an excellent way to launch and codify the work on a new project between colleagues. But it is a terrible way to begin an artistic relationship.

Nightswimming is a commissioning company because we want to work on projects from inception – from the idea that precedes the text or movement. Before we commission any project, we often spend several years discussing ideas with the artist, getting to know the writer and giving them time to learn about us and see our work. Like any company we have a set of artistic preferences and interests and it is vital that the artists we commission be both aware of those and present us with ideas that fit within or directly challenge our artistic desires. This period not only helps evolve the specific project that we ultimately commission; it also establishes trust between partners – a vital element of any and every commissioning relationship.

Our commissions often begin by asking an artist to propose an idea that – because of its form or content or cast size – they would not otherwise be able to pursue. We want them to work on a dream project that they don’t think will fit anywhere else. We are interested in the idea they are afraid of, or have put aside for other, more easily sold projects. Conversations about stories, ideas, form, structure and creative process establish and extend the relationship, and if the right idea emerges – one that fits both their desire to create, and our desire to explore – we offer a commission.

By the time we commission an artist, we know we want to work together and our commission contract marks a commitment on our part to work on the show until its premiere. Only by making a commitment to that extent can we feel we are equals in the relationship. It’s not a gamble, but an agreement between partners to create a new work together, over time, and see that it is produced.

Of course, some of our commissions have not resulted in productions, or even in scripts. In these situations we have mutually agreed to dissolve the commissions. Awkward, certainly, but an agreement that occurred following discussion, rather than a unilateral decision by the all-powerful theatre company.

Our commissions do not include stages at which we decide ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on a project. Drafts that we don’t ‘like’ aren’t a reason to drop the commission. Instead, they are a creative hurdle which we address together. Deadlines are based on the specific creative process for each project, not arbitrary dates set out in a contract. And of course money: we pay the commissioning fee in full at the signing of the contract. Subsequent payments are based on workshops or readings rather than the delivery of drafts. We believe that it is important to pay writers for the time they spend preparing for each workshop and the time spent on subsequent revisions. As a result, our workshop fees for writers are often quite large, but they are intended to take into account significant time for pre-and post-workshop writing.

Does the fact that Nightswimming does not produce these projects make this approach feasible? Yes. We never have to decide whether to produce or not. Because of that Nightswimming and the artists we commission are on the same side, both seeking a premiere production in order to complete the project. That’s why we have designed the company to operate in this manner. We never want to be in an adversarial position with the artists we commission.

Is the play I read this morning what I expected? Not entirely. Is it what I wanted? Yes. It perfectly captures the playwright’s first round of instincts regarding the story he’s telling. Great ideas, new ideas, old ideas and some less than successful ideas jostle one another among a mixture of vivid scenes and a few confusing ones. That’s a great first draft.

But whatever the quality of the first drafts we receive, they are never end points. They are always about the beginning of – or in truth, an extension of – a relationship that began long before the commission was signed.

Thinking back to Morgan’s conference session, here’s what I’ve retained. Don’t commission unless you have a really good reason to do so. We’re very cautious about who and what we commission. There are many pitfalls to commissioning and many alternatives that are just as creative, productive and artful. We’ve evolved a model that is specifically designed to serve Nightswimming’s creative interests and those of our artists. That’s why it works… for us.

This article was first published in The Works, the journal of Playwrights Workshop Montreal. Issue 48, Fall 2006.